Get to Know Gabo

He’s known throughout Latin America, with great fondness, as “Gabo.” The people of his native country of Colombia, South America and his adopted hometown of Mexico City, Mexico regard him with love and reverence. They all claim him as one of their own. He’s influenced writers and readers worldwide as a Nobel Prize winning author. He is a journalist, a mentor to journalists, a movie and television scriptwriter, a movie critic and a passionate advocate for his brand of politics. He speaks his mind and refuses to write or speak in anything but Spanish. Throughout the world, he is larger than life. He is Gabriel García Márquez.

Gabriel García Márquez was born on March 6, 1927, in Aracataca, a village in the Colombian Atlantic coast. He is the oldest of twelve children.

In the Beginning

Gabriel, nicknamed “Gabito” (“little Gabriel” after his father,) was born in March of 1927 in the tiny Colombian banana town of Aracataca. At the time of his birth, bananas were booming. The next year, the banana economy began to unravel and created a rift in the town that has never been repaired. Because his parents were struggling to make ends meet, he was taken in by his maternal grandparents and raised as a part of their family. They were colorful people; his grandfather was an old decorated Colonel and revered by the town and his grandmother, who sold candy animals to support the family, could deliver even the most outrageous, superstitious tale with conviction. They were both great storytellers and the house where they raised “Gabo” was haunted by ghosts. Such is the stuff of the life—and the art—of Gabriel García Márquez.

The Hungry Bohemian

At the age of 19, despite a passion to be a writer, García Márquez enrolled in the law program at the Universidad Nacional in Bogotá, respecting his parents’ desire for him to be “practical.” Hungry for something to keep him engaged, Gabriel began wandering around Bogotá reading poetry instead of preparing for his law classes. He found genius in the works of Franz Kafka, William Faulkner (the most widely translated American writer of his generation,) Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. He began writing. His first novella, Leaf Storm, was rejected for publication in 1952 but later found a publisher in a fly-by-night operation, the CEO of which disappeared shortly thereafter.

The Lover Before leaving his hometown for school at age eighteen, García Márquez met the 13-year-old Mercedes Barcha Pardo and pronounced her the most interesting woman he had ever met. He proposed to her in a fit of passion. At thirteen, she knew she wanted to finish school; she put off the engagement. Though they would not marry for another fourteen years, their love has lasted a lifetime and their marriage is a driving force for García Márquez. She is his muse, his champion. She was as sure of him as he was of her. While he traveled and found himself after dropping out of law school, she waited patiently for him in Colombia until he returned for her when she was 27-years-old.

Garcia Marquez and his wife Mercedes Boat in 1968

The Exile

García Márquez transitioned to journalism after leaving school. He published a sensational but controversial piece about a shipwrecked sailor in Colombia. Worried he might be persecuted the government for his part in the scandalous piece, his editors sent him to Italy. In Europe, García Márquez’ friends and editors kept him “moving” to keep him out of political trouble. In the course of five years he covered stories in Rome, Geneva, Poland, Hungary, Paris, Venezuela, Havana and New York City.He continued to publish stories he believed in, but they made him an exile in his native Colombia and elsewhere. Because of the controversial nature of his political writings, he was not welcome in his own country in 1980. On a highly restricted visa, he was also denied entrance to the U.S.A. from 1962-1996—more than three decades. He was considered by many to be a renegade and a rebel—and he’s never apologized.

Smoking, Scribbling and Success

After a three-year writers’ block that lasted until the beginning of 1965, the personal novel he’d always hoped to write came pouring out of García Márquez. Within a week of the publication of One Hundred Years of Solitude in 1967, all 8000 copies of the original printing had been sold.It was translated into three-dozen languages and won the Chianchiano Prize in Italy, the Best Foreign Book in France, the Rómulo Gallegos Prize and ultimately the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Throughout this success, Gabo kept writing and smoking. He consumed sometimes six packs of cigarettes a day during the furious period of writing One Hundred Years of Solitude. His novels since, both magical and legendary, have kept him at the forefront of literature since 1970: The Autumn of the Patriarch, Chronicle of a Death Foretold, Love in the Time of Cholera, The General in His Labyrinth and Of Love and Other Demons.He continues to write ferocious books with wide appeal. One thing we can promise about García Márquez’s books: you won’t be bored. He garnered vast praise since publishing his aptly named autobiography, Living to Tell the Tale, in 2003. Like his fiction, it has won the hearts of readers everywhere.García Márquez published his most recent work in 2005, a novel called Memories of My Melancholy Whores.

An Interview with Gabriel García Márquez By Gene H. Bell-Villada The following chat with García Márquez took place in his home on Calle Fuego, in the Pedregal section of Mexico City. It was June 1982. His wife, Mercedes—as beautiful and as warmly engaging as rumors say—had opened the front door for me, smiled, and then pointed me toward the inside driveway. “There he is,” she said. “There’s García Márquez.”Curly-haired and compact (about 5’6”), García Márquez emerged from [his] car wearing blue one-piece overalls with a front zipper—his morning writing gear, as it turns out. At this point their son Gonzalo, a very Mexican twenty-year-old, showed up with a shy, taciturn girlfriend. The in-family banter grew lively. In contrast to Gonzalo’s Mexican-inflected speech, the novelist’s soft voice and dropped s’s immediately recalled to me the Caribbean accent of the northern Colombian coast where he had been born and raised.García Márquez and Gonzalo soon led me across the backyard to the novelist’s office, a separate bungalow equipped with special acclimatization (the author still could not take the morning chill in Mexico City), thousands of stereo LPs, various encyclopedias and other reference books, paintings by Latin American artists, and, on the coffee table, a Rubik’s Cube. The remaining furnishings included a simple desk and chair and a matched sofa and armchair set, where our interview was held over beers.Global fame notwithstanding—García Márquez remains a gentle and unassuming, indeed an admirably balanced and normal sort of man. Throughout our conversation I found it easy to imagine him in the downtown café, sipping drinks with the TV repairman or trading stories with the taco makers. He loves to chat; were it not for the cautious screening process set up by his friends and family, he could easily spend his entire day talking instead of writing.

A conversation between novelist Gabriel García Márquez and scholar Gene Bell-Villada, June 1982 in the novelist’s writing bungalow.

Gabriel García Márquez: I wasn’t aware of that fact in particular, but I’ve had some interesting experiences along the way. On one occasion, a sociologist from Austin, Texas came to see me because he’d grown dissatisfied with his methods. So he asked me what my own method was. I told him I didn’t have a method. All I do is read a lot, think a lot, and rewrite constantly. It’s not a scientific thing.

GB-V: There’s a very famous strike scene in One Hundred Years of Solitude. Was it much trouble for you to get it right?

GGM: That sequence sticks closely to the facts of the United Fruit strike of 1928, which dates from my childhood; I was born that year. The only exaggeration is in the number of the dead, although it does fit the proportions of the novel. So, instead of hundreds of dead, I upped it to thousands. But it’s strange, a Colombian journalist the other day referred in passing to “the thousands who died in the 1928 strike.” As my Patriarch says, it doesn’t matter if it’s true, because with enough time it will be!

GB-V: Some critics take you to task for not furnishing a more positive vision of Latin America. How do you answer them?

GGM: Yes, that happened to me in Cuba a while ago, where some critics gave One Hundred Years of Solitude high praise and then found fault with it for not offering a solution. I told them it’s not the job of novels to furnish solutions.

GB-V: You’re a writer with a very intimate knowledge of street life and plebeian ways. What do you owe it to?

GGM: He reflects for a moment] It’s in my origins; it’s my vocation too. It’s the life I know best, and I’ve deliberately cultivated it.

GB-V: With fame, is it hard, keeping up with your popular roots?

GGM: It’s tough, but not as much as you’d think. I can go to a local café and at most one person will request an autograph. What’s nice is that they treat me like one of their own, especially in hotels up in the States, where they feel good just meeting a Latin American. I never lose sight of the fact that I owe those experiences to the many readers of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

GB-V: And which of your books is your favorite?

GGM: It’s always the latest, so right now it’s Chronicle of a Death Foretold. Of course, there are always differences with readers, and every book is a process. I’m particularly fond of No One Writes to the Colonel, but then that book led me to One Hundred Years of Solitude. Excerpted from Gene Bell-Villada’s, casebook on the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Published 01/20/2004

http://www.oprah.com/oprahsbookclub/Books-About-One-Hundred-Years-of-Solitude

****************************************************************************

December 5, 1982 A TALK WITH GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ By MARLISE SIMONS

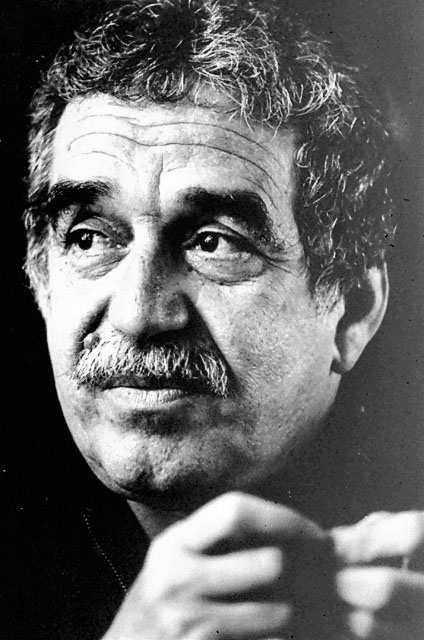

The playful, imperturbable Gabriel Garcia Marquez was troubled and tense. His brown eyes and the large wart over his mustache seemed to have shrunk. He had buried his hands deep in the pockets of his navy blue overalls and paced his hotel room in this small Central Mexican town, where he had come to escape a barrage of well-wishers and journalists.

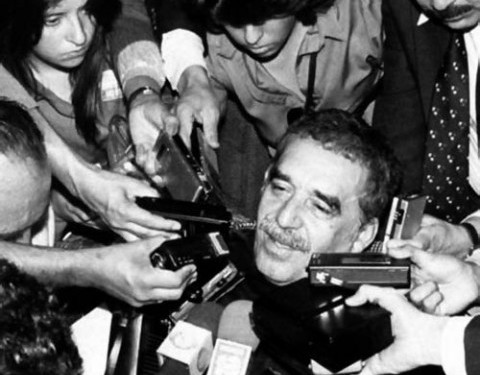

”This is the time I’m supposed to be happier than ever,” he grumbled. ”I’ve just received the Nobel Prize. I’m going to Sweden. I’m famous. I don’t have to work. And look at the state I’m in.”

Garcia Marquez was fretting over the speech he must deliver at the Nobel Prize award ceremony in Sweden on Friday. He had already studied other Nobel speeches for length, tone and content. Researchers, whom he calls ”my ghostwriters,” were digging up facts and statistics on Latin America, not to be used as such but to give him ideas. ”It has to be a political speech presented as literature,” he sighed. ”I envy the chemists and the Peace Prize winners. They don’t have to say a word and everyone applauds anyway.” What’s worse, he muttered on, ”I’ve heard that the Swedish Academy is a solemn clan out to make me over. And I have to wear a tail coat, a colonial costume, an upper-class outfit from the 19th century. I will feel terrible.”

He was what a friend called ”being a Marquezian,” perpetually spinning tales around events, inflating the small and diminishing the sacred to make it less frightening, more manageable. Those who know him well say he lives, talks and writes this way, taking a minor event of the day, tossing, polishing, repeating and expanding it until at the end of the week it has become an epos with a life of its own.

But this 54-year-old man of literature, the storyteller and novelist of the Latin American wondrous, is also a compulsive politician. The politics of the left he practices are as unorthodox as his own freewheeling mind. They express themselves in reactions and sentiments rather than as a coherent doctrine. They surface when he eats, drinks and debates with heads of state, cabinet ministers and guerrilla comandantes with whom he schemes and mediates. The purpose is to promote change, preferably revolution, maybe in his native Colombia, possibly in all of Latin America. When someone recently pointed to the paradox of his friendship with and support for both France’s Francois Mitterrand and Cuba’s Fidel Castro, he said, ”It is logical. Progress in France lies with Mitterrand, in Latin America with Fidel Castro.” In October he acted as an intermediary between Mitterrand and Castro to obtain the release of the jailed Cuban poet Armando Valladares. Mitterrand had been under pressure from conservative French intellectuals for maintaining close relations with the Cuban Government which had jailed the paralyzed poet.

For an author who has long used his literary fame as a vehicle for his political sentiments, there may be few better political platforms than a Nobel award ceremony. Which is why he worried for much of the month of November. ”I have this great opportunity,” he said. ”I must try and break through the cliches about Latin America. Superpowers and other outsiders have fought over us for centuries in ways that have nothing to do with our problems. In reality we are all alone.” Inevitably, perhaps, the author whose recurrent imagery in his writings is that of solitude, was developing the theme of ”the solitude of Latin America.”

Why does Latin America’s most famous author think he was given the coveted Nobel prize? ”For my books,” he quickly replied, brushing aside suggestions that it may be related to politics or geography. ”But I knew I had a strong godfather there, the poet Artur Lundkvist. He is the only member of the Swedish Academy who intensely cares about Latin American literature. For us Latin writers, he was always a fearful, remote deity who determined the fate of our letters. When I met him, he proved to be a very humorous old man with a young heart. He once told me, ‘I refuse to die until they give that prize to you.’ ”

We left the hotel and our car headed through the desert to Zacatecas where the director Ruy Guerra, a friend of Garcia Marquez, was filming his story ”Innocent Erendira.” From the outset the author, who has no pretense of erudition, had said, ”I am a bad theoretician and a bad critic. I prefer to tell anecdotes.”

He tells stories instinctively, with that same flow of the unexpected that runs through his written narrative. Looking at the unlikely sight of a shepherd appearing with his flock among the desert cactus, he said, ”Being a shepherd is always an art. But in Spain they say a shepherd is only good for one thing, for plane accidents. If a plane crashes somewhere, there is always a shepherd who can tell you, ‘It’s over there, I saw it fall with my own eyes.’ ”

Fame – in Latin America he gets a treatment halfway between a movie star’s and a charismatic leader’s – to him is an unrelenting invasion of his privacy and an onerous pressure on his work. ”It has become more difficult to write. You cannot forget that everything you put down goes to an ever larger number of people. Fame is very agreeable, but the bad thing is that it goes on 24 hours a day. It reminds me of Graham Greene, who said the terrible thing about bombings is that you get wounded – but the bombing goes on.”

Yet fame, and the perennial interviews brought on by it, also permits him to talk about the past he has poured into his novels and short stories. He never seems to tire of evoking or exploring it with nostalgia.

Aracataca appears in his mind, his small, hot and dusty hometown in Colombia that became the Macondo of ”One Hundred Years of Solitude.” So does the rambling house where he grew up as the only child among grandparents and aunts, all of whom became characters in the novel’s complex family chronicle. When Gabriel was an infant, his parents, who had 16 children, moved to another town where his father worked as a telegrapher, and Gabriel was left in the care of his grandparents. His grandfather, Garcia Marquez said, was ”a former colonel who told endless stories of the civil war of his youth, took me to the circus and the cinema and was my umbilical cord with history and reality.” Grandmother was ”always telling fables, family legends and organizing our life according to the messages she received in her dreams.” She was ”the source of the magical, superstitious and supernatural view of reality.”

Almost as important perhaps were his days as a journalist in the coastal town of Barranquilla where he began his literary apprenticeship. He was 20 then and wrote, read and debated every day with three other young reporters with literary aspirations. The inseparable quartet met each evening in a bookshop and went on to cafes, drinking beer and rum till deep in the night. ”We would argue at the top of our voices over literature,” recalled one of the four, German Vargas, to whom Garcia Marquez dedicated ”Leaf Storm,” his first book. Along with their own work, the four read and dissected Defoe, Dos Passos, Camus, Virginia Woolf and William Faulkner, the American who has perhaps most influenced Latin American contemporary fiction. All four appear as friends – German, Alvaro, Alfonso and Gabriel – in ”One Hundred Years of Solitude.”

”The whole notion that I am an intuitive is a myth I have created myself,” said Garcia Marquez. ”I worked my way through literature, reading, writing, reading and writing -it’s the only way.” He read the Russians and the great English and American authors. ”I learned a lot from James Joyce and Erskine Caldwell and of course from Hemingway.” But the ”tricks you need to transform something which appears fantastic, unbelievable into something plausible, credible, those I learned from journalism,” he said. ”The key is to tell it straight. It is done by reporters and by country folk.”

His stories, he recalled, often started from one initial visual image. ” ‘Leaf Storm,’ for example, began from a flash of myself as a little boy, sitting on a chair in the living room,” he said. The initial image for ”No One Writes to the Colonel,” he went on, came ”when I saw an old man looking at fish in the market of Barranquilla.” But ”One Hundred Years of Solitude,” his most monumental work, ”traveled in bits and pieces through my head for 17 years. In the end I was able to talk the book. I walked around with its fragments until they burst. Then I sat down and it took me 18 months to write.”

For ”The Autumn of the Patriarch,” ”my only book which I have not lived myself, I read everything I could about Latin American and especially Caribbean dictators over a period of 10 years. On top of that I talked with whomever I could who had a related experience. Then I traed to forget everything and forced myself to work purely from my imagination so that no event could be linked to a real one. But the dictator became the most autobiographical character of all. Excluding the aspect of power, which I have not known, of course, many of my personal feelings, obsessions, ideas, nostalgias, superstitions, are attributed to the patriarch. No doubt there are affinities between power and fame. I think the loneliness of power and the loneliness of fame are much alike.”

Everything in his books and stories has an origin he can identify; he knows what he associated with each image and how he put them together. Many incidents are little games he plays with his family or friends. He once recounted the origins of General Lorenzo Gavilan, a character in ”One Hundred Years of Solitude” who began as a character in ”The Death of Artemio Cruz,” the novel by his close friend, the Mexican author Carlos Fuentes. ”A conscientious reader had written to Fuentes that the fate of Lorenzo Gavilan, one of his characters, had been left unresolved. Fuentes checked and realized it was true. I told Fuentes it could be fixed. So that is why Lorenzo Gavilan, with the belt buckle from Morelia, dies in the Macondo banana workers’ strike.”

The years from age 20 to 30 for Garcia Marquez were a time of hawking manuscripts, of getting good reviews and poor sales. He spent almost three of these years in Europe, a short time in Rome, a longer period in Paris, writing and being dead poor. ”The most important thing Paris gave me was a perspective on Latin America. It taught me the differences between Latin America and Europe and among the Latin American countries themselves through the Latins I met there.” He is still writing stories about the Latin Americans he knew in that period. It has left him with a love-hate relationship with the French, yet he still visits Paris every year.

Nothing exciting, he feels, is happening in West European fiction. The exceptions, he says, ”are Germany’s Heinrich Boll and Gunter Grass. The French are writing the same sort of books every year for the same Goncourt Prizes.” Garcia Marquez, the anti-intellectual, barely disguises his distrust of France’s intellectuals and their ”schematic mental games and abstractions.” Like so many Latin Americans he looks on theory as an enemy, a box that closes off perception and inhibits the mind. While he has a similar distrust for Communist apparatchiks, whom he calls ”communistoids,” he voices this view only privately so as ”not to play into the hands of the Right.”

Latin American literature, he believes, is ”very much alive.” He calls the late Pablo Neruda of Chile ”one of this continent’s greatest poets.” He admires the Mexican novelists Juan Rulfo and his friend Carlos Fuentes. But there are more than 30 young writers in Latin America, he says, who are doing interesting work and he has tried to use his influence to get their work published. Of Argentina’s Jorge Luis Borges he once said that he ”deserves the highest merit because he has done more than anyone for the Spanish language since Cervantes.”

For the past 20 years the author has lived in Mexico City. He went there ”because there was work for him,” recalled the poet Alvaro Mutis, his friend of 32 years. Here in the 60’s Garcia Marquez wrote film scripts and magazine pieces for a living and fiction in his spare time.

But he feels most at ease, he never ceases to say, in the Latin Caribbean, in coastal Colombia rather than in the country’s highlands. When he left the coastal town of Aracataca to go to school in a Colombian mountain town, Zipaquira, and later went to Bogota, the capital, he said, ”I became a foreigner.” Those highlands were part of a Spanish colonial culture – ”solemn, gray and very cold” – and felt like another country to him. They were opposite realms, the highlands, where people are introverted and silent, and the Caribbean, a domain of sensory profusion, of light, heat and quick repartee, a region where facts and reasons embody none of the virtues ascribed to them in the colonial world. In this realm, truth is regarded as one more illusion, just one more version of many possible vantage points and people change their reality by changing their perception of it.

It is from and about this Caribbean condition of mind that he writes. ”People here sense the presence of phenomena or other beings, even if they are not there,” he said. ”These must be influences of ancient religions, of Indians and blacks. This world’s full of spirits you find all over, in Puerto Rico, in Cuba, in Brazil. In Santo Domingo and in Vera Cruz.”

Given his attachment to the Latin Caribbean, it is not easy to explain why Garcia Marquez feels so irresistibly attracted to its apparent antithesis, the United States. This fascination began more than 30 years ago when the Barranquilla foursome not only studied American literature but also avidly examined the styles of American journalism. ”In Colombia, journalism was very heavy then, academic, classic, very Spanish. North American journalism, especially after its experiences in the Second World War, was new and different.”

American open-mindedness and pragmatism appeal to him. He also unabashedly declares that North America’s authors are ”the literary giants of the 20th century” and ”New York is the greatest phenomenon of our time.” In the same breath he defends Fidel Castro’s foreign policy and scorns Washington’s.

His admiration for the United States makes it all the more painful for him that he has had great difficulties obtaining a visa to enter the country since 1960, due to his political views. He has sent his elder son Rodrigo to study history at Harvard. ”There is no way one can relate to contemporary cultural life without going to the United States,” he said. Ironically that is the place ”with the most serious students and the best analyses of my work. Yet the State Department plays this game with me in which I may or may not be able to go there.”

Why does this man of literature invest so much energy in the political activism that has caused the controversies? ”If I were not a Latin American, maybe I wouldn’t,” he said. ”But underdevelopment is total, integral, it affects every part of our lives. The problems of our societies are mainly political. And the commitment of a writer is with the reality of all of society, not just with a small part of it. If not, he is as bad as the politicians who disregard a large part of our reality. That is why authors, painters, writers in Latin America get politically involved. I am surprised by the little resonance authors have in the United States and in Europe. Politics is made there only by the politicians. The era of Sartre and Camus has definitely passed.”

Next month, after the Nobel Prize dust has settled, Garcia Marquez hopes to go back to writing his new novel. Like his last two books it is already taking shape as a rumor, slowly creating a vanguard of its own. ”One Hundred Years of Solitude” was preceded by the publication of small, provocative fragments and became a myth before it came out. ”The Chronicle of a Death,” which is scheduled for publication in the United States next April, was heralded by a publicity extravaganza worthy of a show business scandal. Garcia Marquez has said that he showed the manuscript to Fidel Castro before submitting it to his publisher; ”Castro,” he said, ”is a very cultured, well-read man, with a keen eye for spotting contradictions in a crime story like this.”

Critics of the author ascribe the brouhaha around his publications to his mastery of the calculated special effect. His friends say it is created by the hordes of reporters who are forever seeking him out. But even his friends concede that the author’s claim, widely reported in the mid-70’s, that he would refuse to publish until Chile’s dictator Augusto Pinochet fell, fits into the category of ”calculated effects.” Of his work in progress he is willing to give only a hint. It is ”a happy love story,” he suggests, which may begin with two octogenarians in bed one morning talking and making love.

Next year the author also plans to fulfill a dream when he launches his own newspaper in Colombia. The project clearly appeals to his old yearning for the world of newspapers and to his newer appetite for power through political influence. His own explanation is that he wants to set new standards and train young people for his paper. ”I have always been pulled by the world of journalism. And I am still fascinated by the relationship between journalism and literature.”

Marlise Simons reports for The Times from Mexico and Central America.

http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/06/15/reviews/marquez-talk.html

**********************************************************************

Published: April 10, 1988

THE BEST YEARS OF HIS LIFE: AN INTERVIEW WITH GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ

By Marlise Simons;

Marlise Simons reports from Latin America for The New York Times and is the author of ”The Smoking Mirror: Life in Latin America.”

FOR Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the pleasure and turmoil of writing change from novel to novel. In the case of ”One Hundred Years of Solitude,” he thought so long and hard about the story that when he finally sat down to commit it to paper, it came in a great burst. But he had difficulty writing ”The Autumn of the Patriarch,” a novel he published seven years before he won the Nobel Prize in 1982. With that book, he recently recalled, ”I was doing well when I could finish four lines a day”; the whole project occupied him, off and on, for seven years.

By contrast, the years when he worked on ”Love in the Time of Cholera” were among the happiest of his life. Nostalgically, he wrote about the courtship of his parents and his own journeys by riverboat, both of which were important sources for the book. In Mexico City, his longtime home base, we talked about what writing the novel had been like:

This book was a pleasure. It could have been much longer, but I had to control it. There is so much to say about the life of two people who love each other. It’s infinite.

Also, I had the advantage of knowing the end beforehand. Because in this book, the end was a problem. It would have been in poor taste if one or even both of the characters died. The most wonderful thing would be if they could go on loving forever. So the reader is given the consolation that the boat with the lovers will keep on with its journey, coming and going. Not only for the rest of their lives, but forever.

***********************************************************************

The Visual Arts, the Poetization of Space and Writing: An Interview with Gabriel Garcia Marquez

This interview is the result of two conversations with Nobel Laureate Gabriel Garcia Marquez at his home in Mexico City in 1987. The first meeting, which took place in May was an informal chat, during which Garcia Marquez showed me several nineteenth-century drawings of Colombia by Charles Saffray and Edouard Andre that he had used in writing some of his fiction. (I later found a new edition of the same drawings in Colombia: Fabulous Colombia’s Geography, comp. and dir. Eduardo Acevedo Latorre, Bogot: Litografia Arco 1984.) Encouraged to pursue the dialogue, I returned to Mexico City in October with my copy of Fabulous Colombia’s Geography and a tape recode in hand.Raymond Leslie Williams University Of Colorado Boulder

WILLIAMS: The last time we talked, you showed me the drawings you’ve used in some of your writing. I was impressed with the enormous importance the visual arts apparently have had in your work. As I suppose you know critics have tended to emphasize the literary texts or written documents in your fiction, particularly since the term intertextuality has come into vogue. Do you think we’re missing something with our emphasis on textuality?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: I don’t use written documents. I typically drive myself crazy searching for a document and then end up throwing it mp Then I find it again and it doesn’t interest me anymore I need to have everything idealized. Florentino Ariza’s very concept of love is idealized in Love in the time of Cholera. I have the impression that Florentino has a concept of love that is totally ideal and that doesn’t correspond to reality.

WILLIAMS: Would you say it is a concept of love taken from the literature he has read?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: From reading the bad poets. It is a literary concept from the bad poets. I think I’ve said somewhere that bad poetry is very important because you can only get to good poetry by means of bad poetry What I mean is that if you show some Valery or Rimbaud or some Whitman to a young small-town boy who likes poetry, it doesn’t say anything to him. So to get to these poets, first you have to get through all the bad poetry of the popular romantics, the ones Florentino has read, like Julio Florez [a Colombian poet well known in his homeland (l867-l925)], the Spanish romantics, and so on. I deliberately tried not to cite lot of them because they’re not universally known. Imagine the Japanese reading these books and me talking about Julio Florez. Now I always think of my translators when I write

WILLIAMS: Since One Hundred Year of Solitude?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: NO, since The Autumn of the Patriarch. Since then I’ve received lists of questions from the translators, and what’s strange is that in most of the books they’re the same questions.

WILLIAMS: Let’s return to the visual arts and the fabrication of the nineteenth century in Love in the Time of Cholera.

GARCIA MARQUEZ: I was aided considerably by portraits, photographs, family albums, those kinds of things.

WILLIAMS: Would you say that you have a visual memory? Do you remember things based on what you see?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: I’m not sure if it’s exactly a visual memory. At times it seems like I’m always a little distracted, that I’m a bit off in the clouds. At least that’s what my friends, Mercedes [his wife], and my children say. I give that impression, but then I discover a detail that reveals an entire world to me. The detail could be something I see in a painting. Perhaps the fighting cock in this drawing [fig. 1] could give me the solution for an entire novel. It’s just something that happens to me. I’m totally pas-sive and it’s like a flash.

WILLIAMS: Does this detail tend to be something that you see?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: It is always something that I see. It is always, always an image, with no excep-tions. A politician came and talked to me over a 1ong weekend once in Cuernavaca. We spent the days talking and having a good time. But when he left on Wednesday, I gave him a sixteen-page syn-thesis of our conversation, and not one important matter was missing. It’s not an extraordinary thing but rather an idea 1’ve had for a long time. That’s why I never take notes. I don’t forget things I’m in-terested in, and I forget things right away that don’t interest me. So I have a se1ective memory, which is quite a comfortable thing. Now when I’m correct-ing a book I make notes in the margins for correct-ing later on the computer. The computer has been such an important thing for me. It’s been one of the world’s great discoveries. If they had given me a computer twenty years ago, l would have written twice as many books as l have. For example, I’m writing a piece of theater right no’ and every af ternoon I pull my work out of the printer. I take the pages to bed, I read them, and I make corrections and notes in the margin. Now I have the privilege of making changes in the final page proofs. Before the writer did a last reading on the typewriter and the reader did the first reading on the printed page. There was a big distance between the two. Now I make the last correction on the printed page, as if it were the book.

WILLIAMS: How has this “something that you see” surfaced in your novels?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: When I was writing The Au-tumn of the Patriarch there was a point at which I was struggling a lot. I had a certain idea about the palace, which eventually would appear at the begin- ning, but I just couldn’t get it right. Then I came across this picture in a book, and the photo solved my writing of the novel. It was the image that I needed.

WILLIAMS: It’s the decaying palace and cows described, in the opening pages of the novel.

GARCIA MARQUEZ: And at the beginning of every chapter.

WILLIAMS: Did you use drawings from nineteenth-century travel books in The Autumn of the Patriarch and Love in the Time of Cholera?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: More for The Autumn of the Patriarch than for the other books. I found the idea for some strange images from those drawings; For example images of dead cocks hanging from times, strung up after being killed.

WILLIAMS: Could you explain more about what you did with drawings in The Autumn of the Patriarch?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: I had the idea of creating a to-tal world in The Autumn of the Patriarch. It was a world that hadn’t been very well documented. One would need to read a lot to find out something about the life about daily life Then, by chance, I came across these drawings when I was already writing the book. So it was similar to a Lottery, yet something like that always happens to me. I don’t know why but the truth is, once I begin to Work on a subject, things related to it begin to fall into my hands. Maybe these things were always there and l never noticed them before.

WILLIAMS: Did the drawings serve to describe everyday life better? Better than texts could?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: Better than texts. Texts have a lot of paper. The drawings are like notes for creat-ing the scenes.

WILLIAMS: Setting aside the visual arts for a while, let’s talk about visual images from your own life experiences. What about all those images of the Mag-dalena River in Love in the Time Of Cholera? Were those images from drawings?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: No, not all of them. I had im-portant experiences on that river in different periods of my life, and each experience projected different images that I remembered later’ I traveled on the Magdalena River for the first time when I was eight or nine years old. I left Aracataca for the first time when my grandfather died and I went to the town of Magangue. I made the boat trip to Magangue with my father because he was born in. Since, a town in the department of Bolivar, and we went to visit his mother. I believe it was in l936. When I made the trip that time the boat only went between Barranquilla and Magangue, in over twenty-four hours.

WILLIAMS: It went quickly then.

GARCIA MARQUEZ: No, not really It was a long trip. The boat was wood-fueled, as in the novel. They had to carry the wood aboard. That was when they began cutting all the trees down. Unlike today in those days you could still see alligators in the river, and that was the big entertainment, seeing the a1ligators at the edge of the river with their mouths open to catch butterflies, or whatever. And there were manatees everywhere too. What really impressed me was the way the manatees nursed their young. Those manatees are in The Autumn Of the Patriarch and Love in the Time of Cholera.

WILLIAMS: Do you recall any other particularly memorable images from this trip?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: What impressed me the most were the alligators, the manatees, and the animals strung up, hanging, as in these drawings.

WILLIAMS: Do you remember much from the other river trips?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: I took at least five or six trips down the river from Bogota to the Caribbean coast while I was in high school in Zipaquira. when I went again, in l943, the river had changed. The boats no longer ran on wood, they ran on oil. The river itself wasn’t the same as I had seen it before.

WILLIAMS: The novel with the river, of course, is Love in the Time Of Cholera. What did you do with the river there?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: In Love in the Time Of Cholera I created two trips on the river. The first trip is when Florentino Ariza leaves Villa de Leyva as a te-legrapher. I invented this trip for a technical reason, to avoid describing the river during the second trip, because that would have been too weighty and would have distracted a lot. Consequently, I decided to show the river first through the character him-self, the idea being that the second time around the river would already be described. I didn’t have to distract the reader with too many descriptions of the river.

WILLIAMS: Ail in all, what do you think about the relation of the real river you saw to the one from the Nineteenth-century drawings, as far as your fiction is concerned?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: I was well acquainted with the river back in those days. On the other hand, the drawings helped me realize how for better or for worse, artists idealized everything in the nineteenth century In the drawings you find some fantastic birds that don’t exist, for example Or these women, who are idealized [fig. 5]. You see some beautiful women in these drawings, which is the way the Eu-ropeans of the period imagined them. Indeed, they are magnificent drawings.

WILLIAMS: Many items from the daily life of the period appear in Love in the Time of Cholera, besides the idealizations found in the drawings. These items seem to ref1ect a thorough understanding of what was in fashion at the time.

GARCIA MARQUEZ: I did study those things of daily life in the nineteenth century a 1ot. But you have to be careful not to fall into my trap, because I am also quite disrespectful of rea1 time and space.

WILLIAMS: Are you referring to the anachro-nisms?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: Yes, because I don’t write with historical rigor. Someone could figure out, for examp1e, that Victor Hugo and Oscar Wilde couldn’t have been in Paris at the same time. It’5 not that these are anachronisms or accidents but that I had no desire to change a detail I liked just to make the chronology function properly This novel isn’t a historical reconstruction. Rather, it contains historical elements used poetically All writers do this.

WILLIAMS: The physical space in Love In the Time Of Cholera seems to correspond largely to Cartagena, Colombia, but suddenly the Cafe de la Par- roquia of Veracruz, Mexico, appears. I guess we need to talk about a poetization of space too.

GARCIA MARQUEZ: Right. The Cafe de la Parroquia could be in Cartagena perfectly well. The fact that it isn’t is purely incidental, because al1 the con- ditions exist in Cartagena for it to be there. As a matter of fact, the very same Cafe de la Parroquia of Veracruz would be in Cartagena if the Spaniard who built it had immigrated to Cartagena instead of to Veracruz. It’s just a matter of chance, the way it is was for my wife’s grandfather, who was an Egyptian who left for New York and ended up in Magangue. Well, that was quite a case of the poetization of space–a bit of an exaggerated one. Car- tagena still needs a cafe 1ike the Cafe de la Parroquia in Veracruz, so I took the one from Veracruz, which I needed in Cartagena for my novel. When I’m in Cartagena I sometimes suddenly feel the desire to go to a place like the Cafe de la Parroquia in Veracruz. I have to go to the bars in hotels and places like that, and I feel something is missing. How marvelous to have the freedom to be a writer who says, “Well, I’m going to put the Cafe de la Parroquia where I want it to be” Every day I’m writing I say to myself how marvelous it is to invent life, which is what you do, although within the bounds of some very strict laws because characters don’t die when you want them to, nor are they born when you want. One of the most emotional ex- periences I have had as a writer relates to all this. It happened in Love in the Time Of Cholera, with the family of Fermina Daza, when she is a child. I was creating all her life inside the house where she lives with her father and her spinster aunt, and the house is a copy of the one that is now the Oveja Negra bookstore in the Plaza Fernandez Madrid in Cartagena. I was working on the first draft. I had the girl, her father, her aunt, and her mother, but the mother alwnys seemed extra. I just didn’t know what to do with the mother. When they were at the dinner table, I could see the father’s face perfectly, and I could see the faces of the girl and the aunt perfectly, but the mother’s face was always blurred. I imagined her one way and then another way I made her like, so-and-so, I but she remained a constant problem and I didn’t know what to do. She was ruining my novel. The aunt took the girl to school. The father wasn’t ever home. The maid took care of the house. But what was the mother supposed to do? She didn’t have anything to do. And then sud- denly one day thinking that I was stuck on a deadend road, I realized that what had happened was that the mother had died when the girl was born. And this was the reason the aunt was there because the father had brought her to the household to raise the child when the mother died. And this was the reason too that the maid took care of absolutely everything in the house. And also why the mother had nothing to do in the house. It was a precious ex perience for me, and it explains how the character of the mother began to live the very moment I discovered that she had died. So she is always a pres- ence in the house and the characters speak of her as someone who has died, who has left her mark on her daughter. This a1so explains why the father is so lone1y and has the type of personality he has. I solved everything once I said, “I’m mistaken. I’m trying to resuscitate a dead person. This woman ‘died.” That kind of thing happens in all my books. In some situations you don’t have ally more resources than your own interior world.

WILLIAMS: How would you characterize your relationship with the exterior world, with the city of Cartagena when you were writing Love in the Time of Cholera in l984?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: It was a very amusing relationship. TO begin with, that period in Cartagena was the best year of my life, the most mature.

WILLIAMS: Mature in what sense?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: In the sense of feeling an absolute emotional stability For many years I had only had a vague idea of how l liked to live, but that year I Learned how to live, how I wanted to live and how I have liked to live. When I was living in Cartagena during that time I wrote in the morning, and in the afternoon I would go out conscientiously looking for places because I had two cities: the one of reality and the other one of the novel. The latter can’t possibly be like reality because a novelist can’t Literally copy a city Have you ever noticed what Flaubert did with the distances between places in Paris? You find that the French writers have their characters take walks that are impossible. It’s a poetization of space. Of course, one can sometimes eliminate a totally useless trip, and I did the same thing with Cartagena. Not only that, but when I needed something from another city, I took it to Cartagena.

WILLIAMS: And you took things from several Caribbean cities, right?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: Yes, I took a lot from the Caribbean. There are details from Santo Domingo and Havana, among other cities. That was easy be- cause the cities of the Caribbean have so much in common. AS for Veracruz, Love in the Time of Cholera could take place there perfectly. The only significant difference is that Cartagena has an aristocracy that Veracruz hasn’t had since the Mexican Revolution. Never before had I had what I was writing at hand and been able to go out as if with a sack and put in that sack whatever I waned.

WILLIAMS: And then you could come back to the apartment refreshed.

GARCIA MARQUEZ: NO, weighted down like a sack. And at the same time it was very comfortable because I was living in a calm city set apart from the Caribbean, but with the entire world at an arm’s reach. Almost two or three times a week we had friends visiting from all over the world. And ally time I felt like it I could go to the airport and take off to Europe or New York or wherever. It’s a very comfortable city for that. If I was waiting for some- one arriving on the four o’clock plane, I would go out on the terrace to read, and when I saw the four o’clock plane arriving, I would run to the car and arrive at the airport just as my visitor was coming out of it. Fantastic right? After traveling around the world one realizes how easy it is to live there. And then later the situation in the country changes and one is screwed. It seems to me a great in justice.

WILLAMS: Sometimes when I look at Cartagena from above from the fortress of San Felipe, it seems like a little fiction.

GARCIA MARQUEZ: Well, it’s not possible to define Cartagena. And the historians have invented another Cartagena, which has nothing to do with the real one.

WILLIAMS: And what the historians have to say wasn’t of ally importance to you in this book?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: No. In a nutshell, that was my Cartagena experience. In addition, my geographic and emotional referents in The Autumn of the Patriarch were Cartagena too.

WILLIAMS: Really? I hadn’t ever thought of Cartagena.

GARCIA MARQUEZ: What happened was that I took away the wails because with them the identity of the city would hot been too definite.

WILLIAMS: Cartagena and Veracruz were cities not only surrounded by walls but built by the same Spaniards during the colonial period.

GARCIA MARQUEZ: Yes, but in Love in the Time of Cholera I used a trick when they go up in a balloon and pass over the ruins of Cartagena. Do you remember that? They see the old city of Cartagena abandoned. As an almost poetic image, it’s beautiful, and the use of this image gives an idea of how things can be handled in literature

WILLIAMS: Once again, the poetization of space.

GARCIA MARQUEZ: Exactly, and just when I have them convinced that this is Cartagena, then I take them through an abandoned Cartagena. It’s a dou- bling of the city Let’s say it’s the same city in two distinct periods, two different temporal spaces.

WILLIAMS: We’ve spent most of our time talking about visual arts, your poetisation of space and the like Before leaving behind Love in the Time of Cholera, one last question. Why a nineteenth-century love story?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: In reality, it’s my parents’ love story I heard my father and my mother both talk about these love stories. That’s why the story is set during the period of their youth, although I put much of the story back even further in time My father was a telegrapher who also placed the violin and wrote love poems. In Love in the Time of Cholera I was concerned with the period when the novel ended. Consequently, I made an effort to go far enough back in time that the couple would be eighty y6ars old when the novel ends. If I put them at the end of the nineteenth century, it wasn’t be- cause I wanted to but rather so that they could finish with the trip on the Magdalena River. It had to be a period in which the airplane couldn’t be a solution.

WILLIAMS: Setting aside the novels momentarily, I have a more general question. I remember read-ing about a GARCIA MARQUEZ who always seemed very doubtful about literary critics and academic scholars. Has your age or have other factors changed your attitude at all? Are you more in- terested in what the critics have to say?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: There’s an important change, and that’s that I don’t read them at all now

WILLIAMS: Not at all?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: No. I don’t read them, because I find them very distant. There’s no doubt that the author’s vision of his or her books is very different from the vision of the critic or of the reader. Besides, critics cause a lot of doubts. On the other hand, I’ve had the good luck of having readers who give me great security. For example, books as different as Chronicle of a Death fortold and Love in the Time of Cholera have given me security. Readers don’t tell you why they liked the books, nor do they know why but you feel that they really like them. Of course there are also people who say they don’t like the books, but in general my readers seem to be swept away And my books are sold in enormous quantities, which interests me because that means that they are ed by a broad public They are read by elevator operators, nurses, doctors, presidents. This gives me a tremendous security, while the critics always leave writers with a spark of insecurity. Even the most serious and ptalsefu1 critics can go off on a track you hadn’t suspected, leaving you wondering if perhaps you made a mistake. Besides, I understand the critics very little I’m not exactly sure what they are saying or what they think. The truth is that what really interests me is telling a story Everything comes from inside or is in my subconscious or is the natural result of an ideolog- ical position or comes from raw experience that I haven’t analyzed, which I try to use in all innocence I think I’m quite innocent in writing. If someone studied my books seriously from a political point of view, it wouldn’t surprise me at all if it were discovered that they are completely different from what I say about politics.

WILLIAMS: Let’s finish with a political question of interest to many readers of PMLA. I know that at different times the Modern Language Association and other professional organizations in the United States have questioned the State Department’s handling of your status as a foreign visitor In addition, many US academics would like to see you at conferences and symposia. The details of your status are not clear for many of us. What exactly has been your position concerning our State Department?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: That’s an interesting question because the problem with my entrances and exits and the problem of my illegitimacy in the US are more the US government’s problems than they are mine. I’ll explain why. The reason I’m not totally legal in the United States is because of the McCarran- Walter Act, which prohibits or limits entrance into the United States for some individuals because of their ideas. That’s the serious part. The law is in total contradiction to the Constitution and supposed political philosophy of the United States. Of course, I’m not a terrorist. I’m not even a political activist. I do have political ideas, which I express, although much less than some claim.

WILLIAMS: Well, you and I usually talk about literature.

GARCIA MARQUEZ: I’m very consistent about what I do. Except for having political ideas, I can’t be accused of an act that violates the McCarran- Walter Act. The State Department knows that perfectly well and always has. Consequently, I really can enter and leave the US whenever I want, and I’ve been there from time to time. I was a US resident when I was a correspondent with Prensa Latina in the early l960s. I returned to Mexico when a group of militant Communists who took over the agency decided I wasn’t trustworthy Just look at all the contradictions in this. Then thcy cal1ed me to the US embassy here in Mexico one day and told me to turn in my card and that they would return it to me when I wanted it. Innocently, I turned it in. It would have been far more difficult for them to have taken it from me. They probably could only have done so with a legal battle Then a year or two later I went to a US consulate to get travel papers, and they told me I didn’t qualify. I didn’t try again until l97l, when they gave me an honorary doctorate at Columbia University I discovered I could gain entrance into the US anytime I wanted, but always as an exception, which made me realize that I was solving their prob1em. That is, I was solving the problem of the McCarran- Walter Act for them. As an exception, I always had a litt1e code at the bot- tom of my visa. Besides that, I’m in a “black book,” which must now be a “black computer” Since there are so many people who would 1ike to go to the US and can’t because of this law it isn’t appropriate that I accept the exception they make for me each time. So I don’t accept this visa.

WILLIAMS: And you don’t go to any conferences or symposia in the US?

GARCIA MARQUEZ: Well, I don’t go to any symposia, because I don’t like those meetings and I attempt to avoid all of them. Besides, in the US, I maintain this position on the unacceptable visa. I could have gone to any of the conferences that I’ve chosen not to attend’ They would have given me the visa, but always with the little code on the bottom. It takes a month for me to get the visa, but they always give it to me. There is another matter that is absurdly contradictory. In what other country are my books studied more seriously? I’ve always said that if they’re going to prohibit my entrance they ought to prohibit my books, too. My books are everywhere. I’m totally inoffensive. What’s offensive are my books, since they have my ideas and they are everywhere That’s the reason I say the problem is more the State Department’s than mine.

Notes

l: The dates of the meetings were l2 May l987 and 2l October l987. These two conversations were the fifth and sixth private talks I have had with GARCIA MARQUEZ since meeting him in Bogota in l975; the October conversation reproduced here represents my first published interview with him. The publication dates of the Spanish originals of the novels we discussed are as fOl1ows: One Hundred year of Solitude, 1967; The Autumn of the Patriarch, I975; and Love in the Time of Cholera, l98l. I would like to express my gratitude to John Kronik for his en- couragemcnt and editorial suggestions and to German Vargas of Barranquilla. Colombia, for his helpful efforts on the years to bring me together with his friend in GARCIA MARQUEZ.

2: The Period GARCIA MARQUEZ spent in Cartagena writing for in the Time of Cholera was in the spring and summer of l984. Since then Political and drug-related violence has escalated enormously. GARCIA MARQUEZ currently live in Mexico City and he mentioned to me in one of the l987 interviews that he had not recently returned to Colombia, because no one not, even President Virgllio Barco could give him assurances of his per- sonal safety. The most immediate danger for him would prob- ably be one of the numerous right-wing death squads that have been increasingly active since l986. He returned to Colombia af ter receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature in l982 and regularly during the presidency of Belisario Betancur (l982-86).

3: The severity of the McCarran-Walter Act has been modified since this conversation. In December l987 Congress set tem- porary limits on the government’s right to deny visas for reasons Of national security. A State Department authorization bill provided that no alien could be denied a visa “because of any past, current or expected beliefs which, if engaged in by a United States citizen, would be protected under the Constitution of the United States” (Washington Post 11 May l988). This part of the interview has been included, nevertheless, in order to clarify GARCIA MARQUEZ’s position on the State Department and the US in recent years.

*****************************************************************

The solitude of Gabriel García Marquez

By Gabriel Escobar / Editorial Writer

July 10, 2012

In the epic masterpiece One Hundred Years of Solitude, residents in the village of Macondo at one point forget everything. The practical solution, in a magical place defined by memory, is to put labels on all things:

book cover of One hundred years of solitude

“This is the cow. She must be milked every morning so that she will produce milk, and the milk must be boiled in order to be mixed with coffee to make coffee and milk.”

How poignant (or tragic?) was it to learn this week that the author of these words, Gabriel García Marquez, is now suffering from senile dementia. Confirmation came from his brother, who said the cancer treatment the 85-year-old author received a few years ago quickened his decline.

“In the family we all suffer from senile dementia, and for him it accelerated with the cancer,” Jaime García Marquez said this week in an interview with the Colombian newspaper El Tiempo. “Chemotherapy saved his life, but it also finished off many neurons, many defenses and cells, and the process was accelerated.”

Senile dementia — Alzheimer’s is one of the common forms — is profoundly cruel when it strikes. We have all been touched by it in some way. The silence imposed by the disease on Ronald Reagan meant that he was gone long before he was taken. I suspect that my paternal grandfather, a medical doctor, had a version of it, though the ravages were not as widely discussed then. I was a teenager when I saw him the last time, during a visit to Colombia. He spent his hours in an aimless wander, robbed of the dispassionate intellect that had marked his life.

Is it the same for García Marquez? We don’t know. Because he is an artist, the loss seems somehow more profound. The tragedy for his countless fans is that Gabo, as he is known, is no longer writing. A man who lived for the written word, first as a newspaperman and then as a novelist, is now and forever disarmed of his art. He had been working on the second volume of his autobiography, but the loss of memory — and perhaps the very words needed to ensnare it — have apparently made that task impossible.

I went back and reread an interview he did years ago with the Paris Review, before he received the Nobel Prize for Literature. If you want a sense of how words defined a life, read these:

“When I worked for newspapers, I wasn’t very conscious of every word I wrote, whereas now I am. When I was working for El Espectador in Bogotá, I used to do at least three stories a week, two or three editorial notes every day, and I did movie reviews. Then at night, after everyone had gone home, I would stay behind writing my novels. I liked the noise of the Linotype machines, which sounded like rain. If they stopped, and I was left in silence, I wouldn’t be able to work. Now, the output is comparatively small. On a good working day, working from nine o’clock in the morning to two or three in the afternoon, the most I can write is a short paragraph of four or five lines, which I usually tear up the next day.”

García Marquez has received worldwide acclaim. But that recognition pales in comparison to the veneration he receives in his native Colombia, where he has attained mythic status. Although he is no longer writing, he’s still around, and that matters a great deal. “When we speak with him, we worry a lot about his health,” said Jaime García Marquez. “But we end up profoundly happy because we have him alive.”

Toward the end of One Hundred Years of Solitude, the main character experiences a “flash of lucidity.” In his case, given his long and eventful life, the vivid recollections prove too terrifying. “He was unable to bear in his soul the crushing weight of so much past,” the author writes.

Perhaps García Marquez, a man who believes so much in memory and in magic, will experience a similarly lucid moment. If it happens, he will see his own legacy as vividly as his famous protagonist saw his own life. At that moment he will remember what is universally acknowledged: His words are for the ages.

http://www.dallasnews.com/opinion/columnists/gabriel-escobar/20120712-gabriel-escobar-the-solitude-of-gabriel-garcia-marquez.ece

****************************************************************************

illustration: unknown

Gabriel Garcia Marquez, The Art of Fiction No. 69 Interviewed

by Peter H. Stone

Gabriel García Márquez was interviewed in his studio/office located just behind his house in San Angel Inn, an old and lovely section, full of the spectacularly colorful flowers of Mexico City. The studio is a short walk from the main house. A low elongated building, it appears to have been originally designed as a guest house. Within, at one end, are a couch, two easy chairs, and a makeshift bar—a small white refrigerator with a supply of acqua minerale on top.

The most striking feature of the room is a large blown-up photograph above the sofa of García Márquez alone, wearing a stylish cape and standing on some windswept vista looking somewhat like Anthony Quinn. García Márquez was sitting at his desk at the far end of the studio. He came to greet me, walking briskly with a light step. He is a solidly built man, only about five feet eight or nine in height, who looks like a good middleweight fighter—broad-chested, but perhaps a bit thin in the legs. He was dressed casually in corduroy slacks with a light turtleneck sweater and black leather boots. His hair is dark and curly brown and he wears a full mustache. The interview took place over the course of three late-afternoon meetings of roughly two hours each. Although his English is quite good, García Márquez spoke mostly in Spanish and his two sons shared the translating. When García Márquez speaks, his body often rocks back and forth. His hands too are often in motion making small but decisive gestures to emphasize a point, or to indicate a shift of direction in his thinking. He alternates between leaning forward towards his listener, and sitting far back with his legs crossed when speaking reflectively.

INTERVIEWER How do you feel about using the tape recorder?

GABRIEL GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ The problem is that the moment you know the interview is being taped, your attitude changes. In my case I immediately take a defensive attitude. As a journalist, I feel that we still haven’t learned how to use a tape recorder to do an interview. The best way, I feel, is to have a long conversation without the journalist taking any notes. Then afterward he should reminisce about the conversation and write it down as an impression of what he felt, not necessarily using the exact words expressed. Another useful method is to take notes and then interpret them with a certain loyalty to the person interviewed. What ticks you off about the tape recording everything is that it is not loyal to the person who is being interviewed, because it even records and remembers when you make an ass of yourself. That’s why when there is a tape recorder, I am conscious that I’m being interviewed; when there isn’t a tape recorder, I talk in an unconscious and completely natural way.

INTERVIEWER Well, you make me feel a little guilty using it, but I think for this kind of an interview we probably need it.

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ Anyway, the whole purpose of what I just said was to put you on the defensive.

INTERVIEWER So you have never used a tape recorder yourself for an interview?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ As a journalist, I never use it. I have a very good tape recorder, but I just use it to listen to music. But then as a journalist I’ve never done an interview. I’ve done reports, but never an interview with questions and answers.

INTERVIEWER I heard about one famous interview with a sailor who had been shipwrecked.

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ It wasn’t questions and answers. The sailor would just tell me his adventures and I would rewrite them trying to use his own words and in the first person, as if he were the one who was writing. When the work was published as a serial in a newspaper, one part each day for two weeks, it was signed by the sailor, not by me. It wasn’t until twenty years later that it was re-published and people found out I had written it. No editor realized that it was good until after I had written One Hundred Years of Solitude.

INTERVIEWER Since we’ve started talking about journalism, how does it feel being a journalist again, after having written novels for so long? Do you do it with a different feel or a different eye?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ I’ve always been convinced that my true profession is that of a journalist. What I didn’t like about journalism before were the working conditions. Besides, I had to condition my thoughts and ideas to the interests of the newspaper. Now, after having worked as a novelist, and having achieved financial independence as a novelist, I can really choose the themes that interest me and correspond to my ideas. In any case, I always very much enjoy the chance of doing a great piece of journalism.

INTERVIEWER What is a great piece of journalism for you?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ Hiroshima by John Hersey was an exceptional piece.

INTERVIEWER Is there a story today that you would especially like to do?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ There are many, and several I have in fact written. I have written about Portugal, Cuba, Angola, and Vietnam. I would very much like to write on Poland. I think if I could describe exactly what is now going on, it would be a very important story. But it’s too cold now in Poland; I’m a journalist who likes his comforts.

INTERVIEWER Do you think the novel can do certain things that journalism can’t?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ Nothing. I don’t think there is any difference. The sources are the same, the material is the same, the resources and the language are the same. The Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe is a great novel and Hiroshima is a great work of journalism.

INTERVIEWER Do the journalist and the novelist have different responsibilities in balancing truth versus the imagination?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ In journalism just one fact that is false prejudices the entire work. In contrast, in fiction one single fact that is true gives legitimacy to the entire work. That’s the only difference, and it lies in the commitment of the writer. A novelist can do anything he wants so long as he makes people believe in it.

INTERVIEWER In interviews a few years ago, you seemed to look back on being a journalist with awe at how much faster you were then.

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ I do find it harder to write now than before, both novels and journalism. When I worked for newspapers, I wasn’t very conscious of every word I wrote, whereas now I am. When I was working for El Espectador in Bogotá, I used to do at least three stories a week, two or three editorial notes every day, and I did movie reviews. Then at night, after everyone had gone home, I would stay behind writing my novels. I liked the noise of the Linotype machines, which sounded like rain. If they stopped, and I was left in silence, I wouldn’t be able to work. Now, the output is comparatively small. On a good working day, working from nine o’clock in the morning to two or three in the afternoon, the most I can write is a short paragraph of four or five lines, which I usually tear up the next day.

INTERVIEWER Does this change come from your works being so highly praised or from some kind of political commitment?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ It’s from both. I think that the idea that I’m writing for many more people than I ever imagined has created a certain general responsibility that is literary and political. There’s even pride involved, in not wanting to fall short of what I did before.

INTERVIEWER How did you start writing?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ By drawing. By drawing cartoons. Before I could read or write I used to draw comics at school and at home. The funny thing is that I now realize that when I was in high school I had the reputation of being a writer, though I never in fact wrote anything. If there was a pamphlet to be written or a letter of petition, I was the one to do it because I was supposedly the writer. When I entered college I happened to have a very good literary background in general, considerably above the average of my friends. At the university in Bogotá, I started making new friends and acquaintances, who introduced me to contemporary writers. One night a friend lent me a book of short stories by Franz Kafka. I went back to the pension where I was staying and began to read The Metamorphosis. The first line almost knocked me off the bed. I was so surprised. The first line reads, “As Gregor Samsa awoke that morning from uneasy dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect. . . .” When I read the line I thought to myself that I didn’t know anyone was allowed to write things like that. If I had known, I would have started writing a long time ago. So I immediately started writing short stories. They are totally intellectual short stories because I was writing them on the basis of my literary experience and had not yet found the link between literature and life. The stories were published in the literary supplement of the newspaper El Espectador in Bogotá and they did have a certain success at the time—probably because nobody in Colombia was writing intellectual short stories. What was being written then was mostly about life in the countryside and social life. When I wrote my first short stories I was told they had Joycean influences.

INTERVIEWER Had you read Joyce at that time?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ I had never read Joyce, so I started reading Ulysses. I read it in the only Spanish edition available. Since then, after having read Ulysses in English as well as a very good French translation, I can see that the original Spanish translation was very bad. But I did learn something that was to be very useful to me in my future writing—the technique of the interior monologue. I later found this in Virginia Woolf, and I like the way she uses it better than Joyce. Although I later realized that the person who invented this interior monologue was the anonymous writer of the Lazarillo de Tormes.

INTERVIEWER Can you name some of your early influences?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ The people who really helped me to get rid of my intellectual attitude towards the short story were the writers of the American Lost Generation. I realized that their literature had a relationship with life that my short stories didn’t. And then an event took place which was very important with respect to this attitude. It was the Bogotazo, on the ninth of April, 1948, when a political leader, Gaitan, was shot and the people of Bogotá went raving mad in the streets. I was in my pension ready to have lunch when I heard the news. I ran towards the place, but Gaitan had just been put into a taxi and was being taken to a hospital. On my way back to the pension, the people had already taken to the streets and they were demonstrating, looting stores and burning buildings. I joined them. That afternoon and evening, I became aware of the kind of country I was living in, and how little my short stories had to do with any of that. When I was later forced to go back to Barranquilla on the Caribbean, where I had spent my childhood, I realized that that was the type of life I had lived, knew, and wanted to write about. Around 1950 or ’51 another event happened that influenced my literary tendencies. My mother asked me to accompany her to Aracataca, where I was born, and to sell the house where I spent my first years. When I got there it was at first quite shocking because I was now twenty-two and hadn’t been there since the age of eight. Nothing had really changed, but I felt that I wasn’t really looking at the village, but I was experiencing it as if I were reading it. It was as if everything I saw had already been written, and all I had to do was to sit down and copy what was already there and what I was just reading. For all practical purposes everything had evolved into literature: the houses, the people, and the memories. I’m not sure whether I had already read Faulkner or not, but I know now that only a technique like Faulkner’s could have enabled me to write down what I was seeing. The atmosphere, the decadence, the heat in the village were roughly the same as what I had felt in Faulkner. It was a banana-plantation region inhabited by a lot of Americans from the fruit companies which gave it the same sort of atmosphere I had found in the writers of the Deep South. Critics have spoken of the literary influence of Faulkner, but I see it as a coincidence: I had simply found material that had to be dealt with in the same way that Faulkner had treated similar material. From that trip to the village I came back to write Leaf Storm, my first novel. What really happened to me in that trip to Aracataca was that I realized that everything that had occurred in my childhood had a literary value that I was only now appreciating. From the moment I wrote Leaf Storm I realized I wanted to be a writer and that nobody could stop me and that the only thing left for me to do was to try to be the best writer in the world. That was in 1953, but it wasn’t until 1967 that I got my first royalties after having written five of my eight books.

INTERVIEWER Do you think that it’s common for young writers to deny the worth of their own childhoods and experiences and to intellectualize as you did initially?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ No, the process usually takes place the other way around, but if I had to give a young writer some advice I would say to write about something that has happened to him; it’s always easy to tell whether a writer is writing about something that has happened to him or something he has read or been told. Pablo Neruda has a line in a poem that says “God help me from inventing when I sing.” It always amuses me that the biggest praise for my work comes for the imagination, while the truth is that there’s not a single line in all my work that does not have a basis in reality. The problem is that Caribbean reality resembles the wildest imagination.

INTERVIEWER Whom were you writing for at this point? Who was your audience?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ Leaf Storm was written for my friends who were helping me and lending me their books and were very enthusiastic about my work. In general I think you usually do write for someone. When I’m writing I’m always aware that this friend is going to like this, or that another friend is going to like that paragraph or chapter, always thinking of specific people. In the end all books are written for your friends. The problem after writing One Hundred Years of Solitude was that now I no longer know whom of the millions of readers I am writing for; this upsets and inhibits me. It’s like a million eyes are looking at you and you don’t really know what they think.

INTERVIEWER What about the influence of journalism on your fiction?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ I think the influence is reciprocal. Fiction has helped my journalism because it has given it literary value. Journalism has helped my fiction because it has kept me in a close relationship with reality.

INTERVIEWER How would you describe the search for a style that you went through after Leaf Stormand before you were able to write One Hundred Years of Solitude?